Nuanced Physical Demand Variables in Soccer

In my previous write up, “A Look Into a Pro Team Training Periodization”, I’ve tried to provide a glimpse of what factors go into deciding how, when, and how much a team should train.

Here, I explore the ideas that many variables can be manipulated in training design to affect physical demand outcomes; some are obvious and measurable, others much more nuanced.

Let's dive into some that are very applicable in most training scenarios.

Space & Velocity

The size of practice exercise areas and its impact on the average space between players has a big impact on the type of movement solutions and potential velocities players may employ.

Large spaces between players will encourage more straight line running, and the greater the distance the higher velocity a player may reach. In contrast; without space to build velocity, players won't reach higher speed, but will be forced to stop-and-go much more often. The former scenario leads to a big load on the posterior chain of soft-tissues, versus the latter which causes more stress to the anterior chain.

There's also an impact on the intensity of actions. Small spaces lead to many actions, which can be very metabolically demanding and cause a good leg burn, but the lower velocities mean less inertia and breaking forces. The large spaces lead to less of those actions, but allow for very intense breaking forces when coming to a stop from high speed.

Based on this, I refrain from stating that smaller spaces lead to higher intensity based on time dependent parameters like actions/min. Perhaps the appropriate term in this case is higher density, since more actions are happening within a time frame, but not necessarily more powerful actions.

Time

Duration of exercises, along with work:rest ratios both within reps and sets, and even the total duration of a practice have a big impact on physical outcomes, focus, attention and motor learning.

Paired with the Space variable, time becomes a powerful tool to manipulate physical stimuli. For example; a combination of medium size “small-sided games” and a time range of 2-4 minutes, creates an environment where players will likely work around velocities and metabolic demands that help develop their ability to endure intense moments of the game like maintaining possession while under heavy defensive pressure over a period of time. Because the game is relatively short, within a time range that allows for players to work at a higher intensity than their aerobic threshold, they'll likely do so. They'll also be able to repeat those bouts of higher than normal work, as long as the recovery between these rounds is long enough for their energy substrates to be replenished.

Work:Rest

The work-to-rest ratio (work:rest) concept is a derivative of the time variable based on our understanding of energy production, the substrates involved, and the time it takes to replenish energy storages between bouts of activity.

A very intense action can only be performed at high intensity for a short period of time relative to a lower intensity action. For example: 1v1 defending exercises demand maximum intensity from attacker and defenders, which depends largely on the creatine-phosphate substrate for fastest energy availability and will be depleted quickly within 10 seconds of the beginning of the action. However, once the action is over, and the athlete can produce enough energy by aerobic pathways, creatine can be replenished and will be ready for another high intensity bout within 1-2 minutes. Depending on the athlete's cardiovascular and metabolic health, this can occur more or less quickly, so each athlete may be prepared to repeat the action sooner or later than another, so we use a Work:Rest ratio that heavily favors Rest (between 1:5 and 1:10).

In contrast; when players are performing a passing exercise focused on technical execution where the physical demand isn't as high, this ratio could be flipped to favor work since energy production can be sustained for a longer period of time without depletion. A simple passing pattern, for example, can run for 4-5 minutes and only require 1 minute recovery before a second repetition (5:1 work:rest). At this intensity, it is the athlete's ability to stay focused, directing attention to the motor learning task, that is affected before energy substrate depletion.

All practice exercises also have a work:rest ratio natural to the game demands. For instance; when playing a full field game, athletes go through a variety of intensities from 1v1 interactions, to extended moments of pressure, to walking and jogging while adjusting position away from the ball. This should also be considered, and is part of the reason why a game can be played for 45 minutes before allowing for 15 minutes of recovery (3:1 work:rest).

Technical Execution

This is a simple concept, often overlooked, but also important. Striking a ball from long range demands more from the tissues involved than a short controlled pass. That's so obvious, but we still hear stories of athletes having muscle injuries from performing an excessive amount of shooting from range. For the most part, all athletes can handle a powerful shot without hurting themselves, but as fatigue begins to set in, risk quickly increases along with it.

I generally pay attention to when these powerful actions may occur during a practice. If we start training with a technical passing exercise, we're not likely to have a powerful shot too early before the athlete is prepared to perform it, and if we're ending practice with a finishing exercise for attackers, when fatigue is already partly set on, we may control the amount of reps from each distance to avoid overdoing shots from a stressful range and minimize risk.

Connecting the Dots

The variables listed above are nuanced factors that aren’t necessarily represented in GPS reports. They are factors which need to be considered during the development of a practice session, meaning that collaboration between sports science and technical staff is key for this to be done effectively.

This also requires a great deal of experience with the sport; an understanding of how tactical and technical context may impact decision making, movement solutions, and technical execution.

Possession and Small Sided Games, for example, can vary greatly in intensity depending on the contextual variables or playing environment. A non-directional possession exercise allows for less sharp movement executions than a directional version, partly due to the dynamics of defending and invading spaces present in the directional version but that doesn’t exist in the non-directional one. Playing a SSG to a large goal encourages shooting from further ranges and demands defenders to protect a bigger area with high intensity blocking actions. Downsizing goals will blunt the intensity of those actions.

Often what looks good on paper turns out not so good in practice, so adaptability is essential as well. We must carefully consider variables and their impact during planning, pay attention to the implementation of how the plan translates into reality, and reflect on its outcomes subjectively and against the objective data outcomes of training before making a judgment on how to adapt and improve in the future.

Consistency is a super power when it comes to training. Most of all motor learning, tactical, technica. And physical development tasks require a certain amount of repetitive exposure before improvement will take place, so be aware of too much variability too soon. Eventually; in highly trained teams and individuals, variability itself becomes an important factor, but as with everything else, focus on one step at a time.

This is (one of) the way(s)

There are so many ways to approach periodization, motor learning, and technical/tactical/physical development. I believe one of the biggest shortcomings of many Sport Science professionals is an attachment to the way they like to do things. Overconfidence is the killer of reflection and growth.

Another issue is the pendulum swing towards injury prevention or risk reduction. Sports Science exists to empower athletes to break records and do things that were not possible before. Doing this while management risk is a more appropriate balance since sport will never be devoid of risk.

Your way should be the product of your knowledge, experiences, environment and resources you have at your disposal. Build your system, apply it, and allow it to evolve as unique challenges present themselves.

Questions or comments?

Feel free to send us your questions or comments at support@teamtalo.com.

A Look Into Pro Soccer Team Training Periodization

Do you wonder how pros train and stay fit through the season? Here's a look into the planning, nuances, and application of periodization in a professional soccer environment.

Do you wonder how pros train and stay fit through the season? Here's a look into the planning, nuances, and application of periodization in a professional soccer environment.

Long Term Planning (Macrocycle)

It all starts with the big picture. A high level look at the key dates within a calendar year is enough to identify unique periods with different demands. For example, the NWSL has 3 major periods:

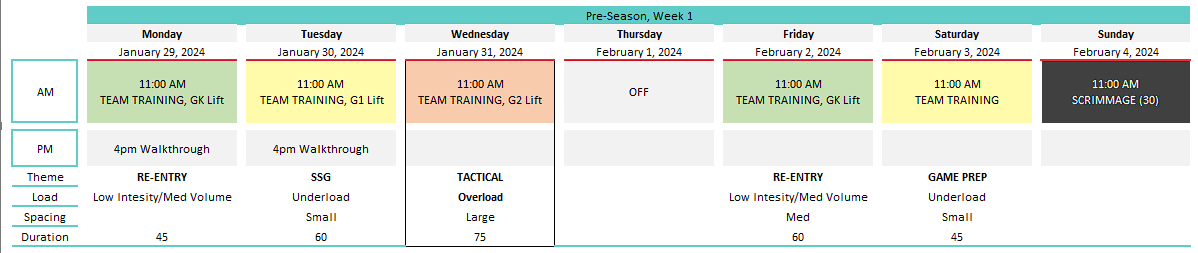

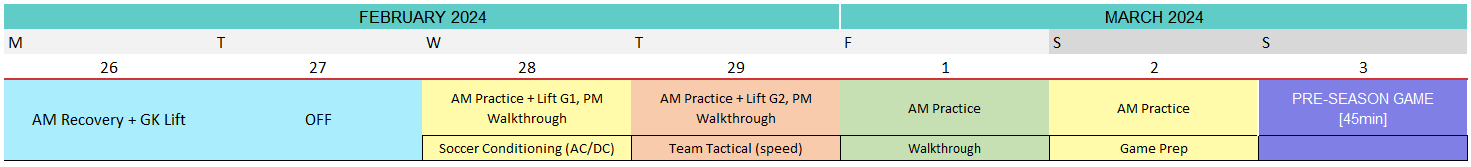

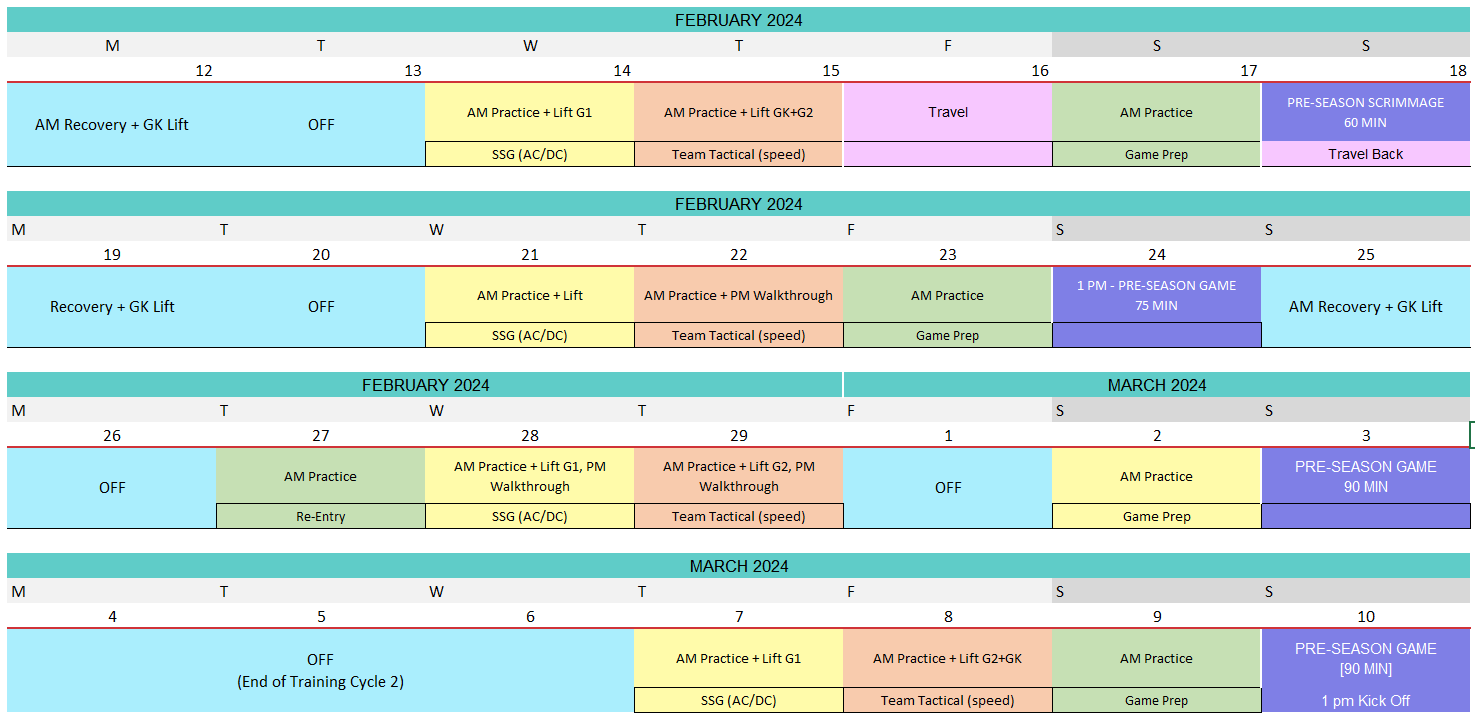

Pre-Season: early period that runs from end of January through mid March (~6 weeks), intended to give teams time to physically prepare for the imminent season.

Season: the competition period, which runs from mid-March through mid-November (if you're good enough to make it that far 😁).

Off-Season: a break period, from mid November through late January, to allow teams and athletes a break from work, vacation time, and for some, a time to recover from issues developed during the season.

Each of the periods above differ in length, allow for different work interactions and interventions, and demand different physical outputs and recovery time.

Training Cycles and Weekly Rhythms (Mesocycles)

From this breakdown, we can begin to dive deeper and develop training cycles and rhythms. This will allow for more details but not quite everything yet.

Weekly Rhythms are the combination of training days and games that repeat within a Training Cycle.

Training Cycles are a sequence of Weekly Rhythms that offer a progressive overload of physical demands to stimulate athletes to adapt to such demands overtime, followed by a longer than normal recovery period to allow adaptations to take place before the start of the next Training Cycle.

Let's look, for example, at the Pre-Season period. There are six weeks available, all players are required to be with the team, and friendly games can be scheduled.

For many of the teams, this is also a time to travel, get away from bad weather, and take time for new teammates and staff to get to know each other.

We could schedule 6 games, since games are what we are ultimately preparing for, each on a Saturday or Sunday, to begin developing a weekly rhythm similar to that of the NWSL games. In the process of scheduling games, opponents’ schedule preferences and traveling dates create challenges to our perfect one week rhythm of game - six days - game, so a variety of Weekly Rhythms begin to form.

The basic Sunday-to-Sunday rhythm may look like this:

Sunday: Game

Monday: Recovery

Tuesday: Off

Wednesday: Training

Thursday: Training

Friday: Training

Saturday: Training

Sunday: Game

This could be repeated over 3 weeks, starting with a relatively easy week of training and short game, followed by progressively harder training and longer games each consecutive week.

But what goes into the decision process for what to do each day?

Weekly Details (Microcycles)

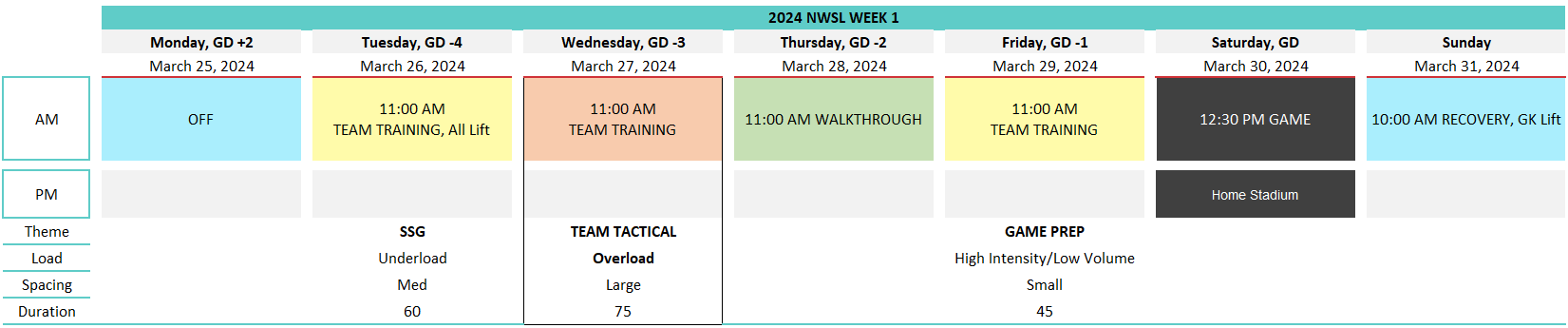

It all starts with the games. If we play on a Sunday, using the rhythm example above, we can begin to build backwards from there using a GD+/- system.

Game Day -1

The day before a game is a day for final tactical adjustments and technical sharpening. We want a quick recovery process following this training, so the volume of training should be low. Depending on the preceding days, it may be appropriate to implement short bursts of high intensity actions here, especially with competitive activities, working as a final rehearsal.

Game Day -2

Two days out we should still proceed with caution. Some highly stressful exercises, such as maximal velocity sprinting, can demand for more than 48hrs of recovery for damaged tissues to fully recover. Since GD -3 and GD -4 are further from the game and ideal for physical overloads, this day most oftenly becomes a day for recovery exercises or low volume/low intensity activities such as Tactical Walkthroughs and Set Pieces.

Game Day -3, Game Day -4

As mentioned above, highly stressful activities lead to 48+ hours of recovery needs. This means that following a game, players would need 2 full days dedicated to recovery, leaving GD -4 and GD -3 as the best options for exercises which will overload athletes physically to drive adaptations.

To make the most of both days, we'll focus on different but complementary movement and energy qualities on each of them. To accomplish this using soccer training, we'll guide the coaching staff on how to adjust variables within their technical/tactical exercises that lead to these specifications.

On GD -3, we will use larger space between players (relative to normal game spacing) to stimulate a higher amount of linear running mechanics, higher maximal velocities, and consequently higher intensity decelerations. However; the increased player spacing will lead to a lower amount of unique actions relative to the duration of the exercise. This simple variable adjustment leads to a greater overload of speed, more stress on the posterior chains of soft-tissues, and an overall increase in intensity.

To compensate for the increased intensity, we will also suggest exercises are built with a high amount of stoppage from coaching during the action or work to rest ratios that favor higher amounts of rest between reps.

Alternatively; on GD -4, we will use tighter spaces between players to stimulate unique actions to occur more often relative to exercise duration. This overload of actions means athletes will need to stop and transition to new movements more often, causing an overload to the anterior chain of soft-tissues as they push the ground away repeatedly.

The repeated changes in action and tighter spaces prevent athletes from reaching high velocities, which means the amount of force required to stop and reaccelerate the body will be lower, blunting intensity levels. Since intensity is relatively lower, we can use work to rest ratios that favor working durations and relatively lower rest periods.

There are many other variables we can and should consider while designing training exercises, so we'll save them for a separate write up.

GD +2 and GD +1

We've discussed the potential need for 48+ hours of recovery after highly demanding activities, and competitive games are as demanding as they will get. So, both days should be used for recovery. However, different scenarios still present themselves within these two relatively simple days.

For example; if GD +1 is following an evening game, it may be wise to be fully off on the following day, since athletes tend to have difficulties with falling asleep after the adrenaline rushes of elite competition. But if the team must travel on GD +1, it may be more beneficial for athletes to go through a recovery session before or after their flights and enjoy a full day off on the following day.

Recovery sessions consist of low stress exercises designed to enhance blood flow to soft tissues while minimizing additional damage. Blood brings nutrients and removes by-products, which are rinsed through the liver and kidneys and wasted by the body. Several other recovery modalities have been tirelessly studied, but ultimately, the most meaningful factors in recovery ability are duration and quality of sleep, hydration, and refueling of essential nutrients.

Questions?

This is a high level view of the planning processes and a simple look at the nuances in it. I plan on writing a deeper dive into the variables that influence physical demands of soccer practices and its exercises, but for now, please feel free to comment with any questions to learn more.